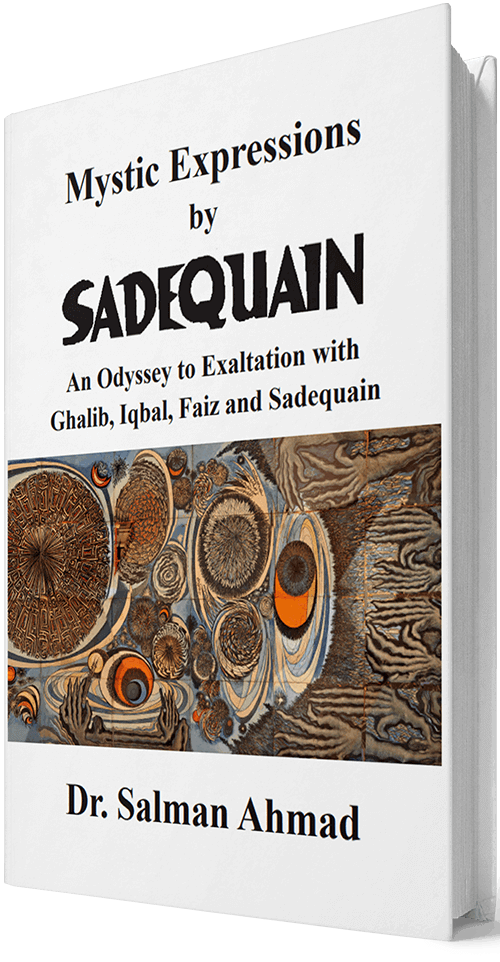

Mystic Expressions by SADEQUAIN – An Odyssey to Exaltation with Ghalib, Iqbal, Faiz, & Sadequain

This book is the first of its kind, which presents a collection of Sadequain’s illustrations and interpretations based on the select poetry of Ghalib, Iqbal and Faiz. The extraordinary collection of 53 illustrative paintings and two large murals by Sadequain included in this book represents a confluence of the most extraordinary talent of the art and Urdu literature. The verses that Sadequain selected to illustrate reflect various states of self-realization and consciousness. As archetypal expressions of mystic vision, these paintings transcend our latent susceptibilities. They hold a beacon to the path of enlightenment, guide through the gateway of spiritual freedom, and provide a conduit to transpersonal truth. In these paintings, Sadequain seeks to share his observations, experiences, and interpretations of the truth, and his relationship to the world around him and beyond through the poetry of his choice.

Sadequain is known to have painted day and night all through his life. It is estimated he painted over 15,000 pieces. He recklessly gave much of his works away, great numbers were taken away, and the remaining were stolen. He did not keep an inventory and traces of most of the works do not exist. The SADEQUAIN Foundation has been engaged in exhaustive research to locate Sadequain’s murals, paintings, calligraphies and drawings, and to this day continues to do so. This book presents the illustrative works based on the poetry of Ghalib, Iqbal, and Faiz that have so far been discovered by the Foundation.