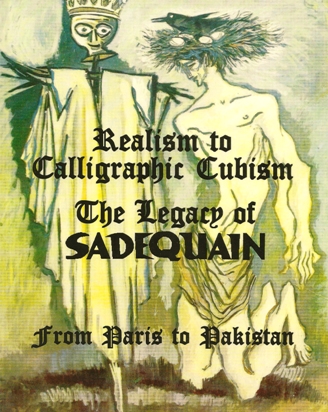

Realism to Calligraphic Cubism – Legacy of SADEQUAIN

The decade of the 1960s represents the most explosive period of Sadequain’s artistic genius, when he defined new idioms and developed his unique iconography while living in Paris, France. He invented new artistic forms, which, it can be argued, had not been explored before. Yet, this phase of Sadequain’s odyssey remains most elusive, because majority of his work of this era remained locked in the attics and basements of Parisian galleries and homes.

The decade of the 1960s represents the most explosive period of Sadequain’s artistic genius, when he defined new idioms and developed his unique iconography while living in Paris, France. He invented new artistic forms, which, it can be argued, had not been explored before. Yet, this phase of Sadequain’s odyssey remains most elusive, because majority of his work of this era remained locked in the attics and basements of Parisian galleries and homes.

From the beginning of 2008 and lasting through 2010, there was a flurry of activity in the sale of Sadequain’s artwork in France. All the sellers of the artwork were French nationals. This begs the obvious question: what prompted this sudden burst of activity after more than 40 years since Sadequain left several hundred, or perhaps thousands of pieces of his artwork in Paris for safe keeping? Equally important, where did the artwork come from, what was its exact source?

In December of 1960, Sadequain was invited to France by the French Committee of International Association of Plastic Arts. He was awarded a stipend for six months to live and work in France. In the absence of historical notes, it is assumed that the invitation from the French organization was under a cultural exchange program. Sadequain extended his initial visit of a few months to seven years of intermittent living and working in Paris, during which period he executed thousands of paintings and drawings.

This book is a chronological trail of Sadequain’s incredible journey from Karachi, where, at early stages of his career, he diligently experimented with realist pen and ink endeavors, and a decade later moved to Paris, where he invented ground breaking fresh forms of calligraphic cubism. These stunning calligraphic forms defined Sadequain’s future work and established him as a master in the same vein as Picasso is considered as the father of cubism or Monet is credited for initiating the impressionist movement.

A major portion of this book is based on translation of Sadequain’s letters which he wrote to his family during the 1960s when he was residing in France and traveling within Europe and to the USA. This book will also establish that Sadequain, while still residing in Paris during 1967, left for Pakistan on an unscheduled visit for personal reasons and left behind a great number of paintings and drawings in custody of his acquaintances and gallery owners in Paris for safe keeping. These paintings remained dormant for decades until the price of his artwork started to rise dramatically in the first decade of the 21st century. At this juncture, the safe keepers of Sadequain’s artwork, who never made an honest attempt of returning the artwork to Sadequain’s family, were lured into cashing in the windfall. Sadequain, as is widely known, did not sell his art. “What, sell art like vegetables?” he questioned when another prominent artist contemplated and proposed establishing a commercial gallery in partnership with Sadequain during the 1960s. Thus the question: if he did not consider selling his art, then why would he condone others to sell it, especially those who acquired it through dubious means?

One of the mourners at Sadequain’s burial in February 1987 poignantly stated that, Sadequain left behind no immediate family – father, mother, uncle, aunt, brother, sister, wife, or children. Granted, that normally it would be the responsibility and duty of the immediate family to preserve the legacy of a person. But Sadequain was not an ordinary person. His donations to the nation and its citizens amounted to hundreds of millions of dollars, a deed unmatched in our society. He has been called a national hero and his work has been branded as national treasure. Then, is it not the responsibility of the nation and its citizens to lay claim to his legacy he left behind in France? The misappropriation in France has been at such a large scale that it warrants attention at the highest levels of the State. A private individual, member of Sadequain’s family or otherwise, simply cannot summon sufficient authority to check the transgressions.

Two examples are cited here to elaborate on the point; one that demonstrates the resolve of the government machinery in the case of one artist, and in the second case, actions by the family of the second artist. In both cases, the actions were aimed at checking the uncontrolled trafficking of the artwork of the two important artists of their respective countries. In 2008, the New York Times reported that the government of Mexico intervened and issued an injunction against an art dealer in New York, when he claimed to have discovered a collection of previously unknown paintings by Mexican artist Diego Rivera, and attempted to sell them. The Mexican government claimed that the artist was country’s hero and as such his artwork was considered national heritage. In the second case, the Times of India reported that after the death of artist Tayyab Mehta, his family approached the Indian courts to claim a portion of all proceeds from the resale of Mehta’s artwork, even if the artwork had originally been purchased legitimately by the seller.

At stake in both cases cited above, was the legacy of the men, their art, and national treasure. Scholars, scientists, writers and artists of merit are trend setters, and they function at a much higher intellectual plane than most technocrats or other functionaries do, no matter how highly placed and how efficient the functionaries might be. All managers, administrators, businessmen, diplomats, or bureaucrats are replaceable. But geniuses like Einstein, Shakespeare, or Michelangelo cannot be replaced. “You cannot train a genius,” Sadequain used to say. Those, who constitute the intellectual elite, can define the future of the nation and mold the intellectual direction for its masses. Without their innovative contributions, the nation as a whole may lumber along toward stagnation, but would not be able to ascend to higher plateaus. Nations are differentiated and recognized by their innovations, creations, and distinguished and unique cultural and intellectual attributes. Without this unique differentiation, the identity of a nation would be lost. It is therefore incumbent upon nations to safeguard the intellectual property of its national heroes.

True geniuses like Sadequain focus like a laser on their passion, but do not pursue commercial gains. Sadequain in particular – rightfully or not – considered commercialization of his art beneath him. Poet Ghalib was not particularly careful with the preservation of his poetry. A recent example of neglect of intellectual property is the case of poet Jon Elia of Pakistan. He was, to his detriment, careless with his work and did not compile or publish it in his life. It was only after his death that Mumtaz Saeed, one of Elia’s close friends, relative, and a scholar in his own right, gathered Elia’s poetry and published it in three volumes, which have since been assessed as a significant contribution to the Urdu literature. If it was not for the dedication of this admirer, Elia’s work would have been lost permanently. Similarly, if it was not for Theo, the world would not have perhaps recognized the genius of the artist Vincent Van Gogh.

In its publication of August 2007, English language magazine Herald compiled a list of 60 heroes of Pakistan in its 60 year history. This list did not include functionaries of government or private organizations. All 60 names that made the list had contributed to the national prestige, knowledge base, and intellectual advancement. What made these heroes worthy of mention was not their business acumen, wealth, or ordinary day-to-day service in the field of their specialty, but it was their innate talent and originality of thought in their respective fields. By pure and relentless application of their talent, they advanced the knowledge of their areas of expertise, which in turn contributed to broadening of the scope of their discipline, and importantly, added to the prestige of the nation. Sadequain was included in the prestigious list of Pakistan’s heroes. But he embodied what F. Scott Fitzgerald said, “Show me a hero and I will write you a tragedy.” More on this subject later.

Mural art is not everyone’s cup of tea, therefore only the most accomplished artists excel in this genre. Sadequain introduced monumental murals to the visual vocabulary of Pakistan. He painted more than 45 gigantic murals, most of which are now housed in Pakistan, India, the Middle East, Europe, and North America. These murals represent unparalleled body of artistic genius by an artist of the region. Most murals were given as gifts to the public institutions. He re-defined the script of calligraphic art during the 1970s and was responsible for the renaissance of this genre in Pakistan. He received unanimous acclaim in the Middle East and East European countries for his innovative painterly calligraphic compositions. During his one year stay in India in 1982, Sadequain painted more than 7 large murals, scores of calligraphies, and exhibited his calligraphic work in a dozen cities at an average of one exhibition every month. He is the only artist from India or Pakistan who is on display at public institutions across the border in the rival countries. No other Pakistani artist is on public display in India and no Indian artist is on public display in Pakistan. All Sadequain’s murals, paintings, and calligraphies done in India were donated to institutions and individuals as a gesture of generosity and good will. By doing so, Sadequain initiated Aman Ki Aasha (hope for peace) long before it became a slogan of necessity during 2010.

This is the kind of stuff that legends are made of. This is the legacy of the man. Legacy is what someone is remembered for, something that is handed down from one period of time to another period. But what would Sadequain’s legacy be if his contributions are hidden from the public, not documented, not preserved and not recognized. Whose responsibility is it to ensure that his legacy is preserved and the legend lives on? Obviously those institutions and individuals, who have benefited immensely from his donations amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars, should shoulder the responsibility and initiate the effort, which has been long overdue.

This book is an attempt to discover Sadequain’s work during the 1960s and catalog it, especially the artwork he did and left behind in France. It was a historic accident. Without this catalog, students of art, art lovers, scholars, and above all the nation as a whole, would remain oblivious to some of the most significant work of a national hero.

This book consists of 4 sections.

Section 1 titled, Realism to Calligraphic Cubism, is an overview of Sadequain’s work during the decade of the 1960s. It traces initial development phase, which after exposure to the world’s leading artists in Paris, crystallized into unique forms, aptly termed, calligraphic cubism. This was the most productive period of his career. Sadequain spent majority of the decade of the 60s in Paris, making his work of that period as the most defining body of his portfolio. But large numbers of this critical body of work fell in the hands of those who treated it as money making machine. How ironic for the artist, who did not want to sell his work and hence preferred to die penniless by choice. But a bigger travesty is that Sadequain’s work of his most critical period is not documented properly.

Section 2 titled, Legacy of Sadequain – From Paris to Pakistan, is a translation of Sadequain’s letters he wrote from Paris, other European countries, and the USA to his brother, Kaz-e-man, in Pakistan. He wrote letters at regular intervals of 3 to 4 days apart and they read like daily diary entries. These are candid details of Sadequain’s daily activities; what he had for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, how many paintings he painted, which paintings were exhibited, and if any were sold. From the perspective of this book, the gist of the letters based on what Sadequain wrote, is that nobody legitimately acquired as many paintings from Sadequain as have been sold in France during the period in question by a small group of people. The only conclusion one can draw is that the paintings that were sold during the period from 2008 to 2010 were the ones that Sadequain left behind when he left Paris for Pakistan on what he thought would be a short visit. But he never returned. Did he ever try to retrieve his work or attempted to have it shipped to Pakistan? We would never know. Did those people, who possessed his work, attempt to return it to Sadequain on their own good will? At least one of them made this claim to the SADEQUAIN Foundation, but the claim sounded hollow and unsubstantiated.

Section 3 titled, Albert Camus and Sadequain, contains a summary of the novel, The Stranger, authored by the Nobel Laureate, Albert Camus of France. This summary provides a perspective of the novel with respect to the lithographic images that Sadequain painted to interpret the story line. According to Sadequain’s letters, he painted a total of 170 lithographs. But only a fraction is contained in this book, because the remaining images were not available.

Section 4 titled, SADEQUAIN is an overview of Sadequain’s prodigious oeuvre, his output of almost 40 years. It is hoped that this overview will be useful to those who are engaged in research on Sadequain and so far have been disappointed for not being able to access historical information. The demographics of such researchers include students from high school to doctoral levels, collage and university professors, free lance writers, journalists, art enthusiasts, and art galleries.

At the end, it is fervently hoped that the concerned authorities would take notice of the misappropriation of the arts and artifacts of the nation and take concrete steps to preserve its cultural heritage.