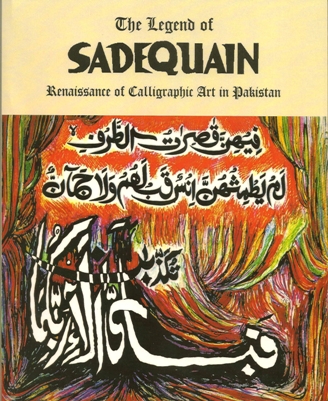

The Legend of SADEQUAIN

This book, the first of its kind about Sadequain, presents a collection of his calligraphic masterpieces. It also provides insight into Sadequain’s unique and unconventional lifestyle. Sadequain is the most written and talked about artist of Pakistan. Many writers and critics have expressed their opinions, praises, critiques, interpretations, and suppositions about his work. One common element, which is missing in most of these commentaries, is that, they seldom take into consideration what Sadequain himself had to say about his work. The focal point of this book is Sadequain’s magnanimous persona, his eventful life and amazing calligraphic work, in many cases presented in his own words. Not to upstage the soon-to-be-published biography of Sadequain by the SADEQUAIN Foundation, this book can be viewed as a preview of that all-encompassing biography. What this book does not attempt to provide, however, is a critical analysis of his work. It simply records the material in a manner that can frankly be defined as “tell-it-like-it-is.”

This book, the first of its kind about Sadequain, presents a collection of his calligraphic masterpieces. It also provides insight into Sadequain’s unique and unconventional lifestyle. Sadequain is the most written and talked about artist of Pakistan. Many writers and critics have expressed their opinions, praises, critiques, interpretations, and suppositions about his work. One common element, which is missing in most of these commentaries, is that, they seldom take into consideration what Sadequain himself had to say about his work. The focal point of this book is Sadequain’s magnanimous persona, his eventful life and amazing calligraphic work, in many cases presented in his own words. Not to upstage the soon-to-be-published biography of Sadequain by the SADEQUAIN Foundation, this book can be viewed as a preview of that all-encompassing biography. What this book does not attempt to provide, however, is a critical analysis of his work. It simply records the material in a manner that can frankly be defined as “tell-it-like-it-is.”

Sadequain is the most prominently visible artist of Pakistan, made so by among other things, his intellect, monumental murals, ingenious calligraphic work, and his ever-so-giving nature. Upon the mere mention of the name “Sadequain,” the response would invariably be: “You mean the calligrapher.” Sadequain and calligraphy are synonymous in Pakistan. One can drive around the metropolitan cities of Karachi, Lahore, or Islamabad and spot calligraphic inscriptions on private residences, businesses, and billboards, imitating Sadequain’s distinctive handwriting — a distinction reserved only for Sadequain — and a novel way for citizens to pay homage to the country’s most celebrated artist. It is homage to his revolutionary style indeed, for which he set aside the old traditions of the established calligraphic scripts and invented his own distinctive iconography, often referred to as “Khatt-e-Sadequaini.”

In a short period of time, Sadequain turned the calligraphic world upside-down and ushered in a calligraphic revolution in the country that created a wave of aspiring calligraphers, now engaged in new experiments and thus redefining the centuries-old art form. What is most unusual to comprehend in this materialistic age is that he gave all of his calligraphic work to institutions and individuals without compensation.

Based on the stated facts, one might assume that art historians would document such a significant impact on the calligraphic art and that Sadequain’s calligraphic art would be cataloged in some form for posterity. However, the reality is otherwise. Thousands of Sadequain’s calligraphies and dozens of his humongous calligraphic murals, which he claimed would stretch for miles if strung side-by-side, and if spread around they would cover several acres, now lay dormant at institutions or private residences. Scores of them have disappeared under dubious conditions, leaving no trace behind, and yet no official authority has registered a complaint or conducted an enquiry.

The individual sections of this book illuminate various aspects of Sadequain’s life and work. The section titled “Renaissance of Calligraphic Art” presents a historic perspective of Sadequain’s contributions to the calligraphic art in Pakistan, and establishes him as the pioneer of this art form, which can justifiably be called the pride of Islam. The sections called “The Legend” and “Legendary Work” record the sequence of events that led Sadequain on his historic journey to the revival of the calligraphic art in Pakistan and identify several examples of his legendary work.

Much has been said and written about Sadequain in the past. However, not much literature can be found about what Sadequain said about himself. It would only be fair to hear him out — how he explained his work in his own words. The section “Sadequain on Sadequain” is a verbatim quote of how Sadequain viewed his work.

Sadequain was the most exhibited artist of his era. He believed that to paint was a service to the arts, and that his artwork was not meant to be displayed at the ostentatious residences of the rich and powerful, but rather be accessible to all, rich or poor, irrespective of their social class. Not interested in material gains, he was averse to the glitter of money. He traveled to foreign countries at the invitation of the hosts, and displayed his works in the most flamboyant style. The section “Calligraphies Without Borders” is a colorful description of a portion of his tour of the Middle East and East European countries, perhaps the most extensive exhibition tour undertaken by any artist of Pakistan, during which he visited approximately two-dozen countries in a span of several months. In spite of the tour’s high visibility at the highest official levels, Sadequain prepared for the event in his own characteristic style, mixing business and pleasure at an extreme level.

The next three sections, “Preparation for Exhibition,” “Close Call at the Exhibition,” and “Exhibition in Dubai,” describe the details of Sadequain’s most unconventional style of preparation for the exhibition, illustrate the last-minute close call due to the unavailability of essential items needed to display the artwork (and that too in a foreign country) and finally paint a picture of the carnival atmosphere of the exhibition.

The historic city of Lahore has been a center of arts and culture for centuries. Sadequain realized that distinction, and occasionally wrote about it. As a practical tribute to the city, Sadequain spent a good portion of the ’70s in the city and painted miles of calligraphies and acres of paintings, and donated them all, “on behalf of the wheat-colored beauties,” to the citizens of the city. “Lahore Factor” captures Sadequain’s sentiments about the city, in which he openly admits its rich contribution to his art.

His days were colorful and the nights were young. Sadequain never rested, hardly ever slept, and his doors were always open to all. No one left his company empty-handed, and he had no lack of curious crowds surrounding him round the clock. The Lahore Museum was his studio, residence, and court in the early ’70s, where he worked, slept, and hosted his audiences. The section “A Day at the Museum” provides a glimpse into his round-the-clock activities when he resided at the museum (perhaps it is a unique event in itself, when a private resident converts a historic museum into his living quarters). It can be argued that he was among the most precious attractions on display at the museum, while he called it his workshop.

The violent demonstrations in Lahore against Sadequain’s exhibition in May of 1976 were the most shameful acts against an art display in the history of the country. The section “1976 — A Summer to Remember” describes the regrettable incidents aimed at Sadequain by extremists, when there were widespread protests in the streets, debates in the parliament, editorials in the newspapers, that eventually culminated in a bomb blast in his exhibition.

“Indian Homecoming” describes one of the proudest moments for Sadequain, when he returned to his ancestral home and painted the country with his calligraphies. During his year-long stay in India during 1982, he held, on average, one exhibition of his fresh work every month, and painted more than half a dozen murals, all presented free of cost to the citizens of the country. Sadequain produced more work in one year in India than any mortal would produce in a decade, if that.

The section “Farewell Gift to Faisal Mosque” registers the events leading to the execution of the last piece of Sadequain’s work, which he gave as a gift to the Faisal Mosque. It provides a revealing view of Sadequain’s fortitude and free spirit.

“A Word About Calligraphy” is a brief description of the sacred art and its historic background. A description of the popular styles of Arabic calligraphic scripts is included in the appendix section.

Art does not flourish in a vacuum. It can be argued that even the Word of God requires a messenger to spread it. The reality is that, art will flourish under the patronage of key institutions and individuals, otherwise it would starve and suffocate. The section, “Patrons of Art — Golden Period of the Mughal Rule,” addresses the significance of the widespread support for art during the Mughal period. It provides an overview of the magnificent advancements in the calligraphic art of that era. Emperors Jahangir and Shah Jahan were great patrons of art, and they ushered in the golden era of innovative calligraphic art by inviting and supporting local and foreign artists, who produced some of the most magnificent pieces of calligraphic art throughout the empire.

The section titled, “The Great Divide,” measures the impact of the division of the Indian sub-continent on the Muslim nation. Scores of people crossed the borders and had to struggle to find refuge in a new homeland. The upheaval had a profound impact on the uprooted population, and it also affected the arts and literature of the period.

“The Final Word” concludes that the state of calligraphic art was in dire straits during the British rule in the sub-continent and it displayed no improvement after the partition during the decades of the ’50s and ’60s. But after Sadequain infused a new spirit in this art form by adapting it in the late-1960s, it started to flourish and soon became the most popular art form, as many senior, as well as young and aspiring artists started to practice it with passion.

One significant section of this book is comprised of the collection of Sadequain’s select quatrains in Urdu language, which he composed as a response to the unruly reaction of the extreme right-wing parties to his exhibition of paintings in Lahore in May 1976. The section, “Revisit to the Controversy in Lahore,” recaps the events of the violent protests, followed by a simple translation in English of the corresponding Urdu quatrains. These quatrains illustrate Sadequain’s prowess of the Urdu language, clarity of thought, and command of poetic expression. In his rebuke of the extremists, he argued that his foray into figurative painting and inscription of the religious calligraphies were both rooted in his genetic composition to seek enlightenment in the beautiful face of mankind. He argued that he did not praise the human body because of lust, but because he did not differentiate between the praise of the Creator and praise of the Creator’s creations.

Included in this book is a collection of more than 160 images of Sadequain’s calligraphic masterpieces. This is the first-ever collection of his work in book form, which provides the viewer with an astonishing array of style and content. Although it is widely known that Sadequain painted thousands of calligraphic pieces, their inventory is not available. Because he simply gave away his work with utter disregard for record keeping, no traces are available of their eventual disposition. Therefore, this book is by no means a retrospect of his work. On the contrary, it only represents less than one-tenth of one percent of his total output. But it still merits the claim to be the first of its kind.